THE ENGELS OF SWITZERLAND

The following text is based on the illustrated lecture commissioned by the Engle Family Association and delivered on June 26, 2004, at the Engle Family Reunion, held in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. An expanded and documented version of this text will appear in a book coauthored by David Rempel Smucker and John E. Engle and commissioned by the Engle Family Association. Projected to appear in 2006, this book will cover Engel family history in Europe and the early generations in Pennsylvania.

A

list of terms and their definitions appear in a separate

reference window. This version on the website omits documentation

in footnotes.

David Rempel Smucker does freelance historical and genealogical research, writing, and editing. From 1981 to 2003 he was employed at the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, primarily as editor of Pennsylvania Mennonite Heritage, an illustrated quarterly. He received a B.A. from Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, in 1971, and a Ph.D. in Christian Church History from Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts in 1981. In 1985 and 1986 he and his wife Judith lived in Basel, Switzerland. She studied graphic design; he did genealogical research and gathered materials for the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society library. In 1988 he completed the German script seminar at Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He has written various articles on topics of Mennonite and Amish history. From 1983 to 2004 he sang in a small group performing a musical drama entitled Menno Heirs, based on the text and tunes of an 1804 Mennonite hymnal. He and his wife, a Canadian citizen, and two teenage children live at 916 Walnut Street, Akron, PA 17501 and attend a Mennonite congregation in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. David Rempel Smucker does freelance historical and genealogical research, writing, and editing. From 1981 to 2003 he was employed at the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, primarily as editor of Pennsylvania Mennonite Heritage, an illustrated quarterly. He received a B.A. from Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, in 1971, and a Ph.D. in Christian Church History from Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts in 1981. In 1985 and 1986 he and his wife Judith lived in Basel, Switzerland. She studied graphic design; he did genealogical research and gathered materials for the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society library. In 1988 he completed the German script seminar at Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He has written various articles on topics of Mennonite and Amish history. From 1983 to 2004 he sang in a small group performing a musical drama entitled Menno Heirs, based on the text and tunes of an 1804 Mennonite hymnal. He and his wife, a Canadian citizen, and two teenage children live at 916 Walnut Street, Akron, PA 17501 and attend a Mennonite congregation in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

The European background of Ulrich Engel and Anna Brächbühl is found in Switzerland, a fascinating country – little understood for as often as it is visited – with four official languages: German, French, Italian, and Romansch. (Only about 40,000 people speak Romansch, less than one percent (0.6%) of an already small country of about 7 million people.)

|

| Map showing the cantons

of Switzerland on which the Emmental Region is

highlighted. This map links to excellent information

about Switzerland provided by Lonely Planet. Reproduced

by permission of Lonely Planet Publications, from

the Lonely Planet website. |

The first reports we know of these Engle ancestors come from the German-speaking part of Switzerland in the rural part of Canton Bern (canton is a political territory like our states and Canadian provinces) in the hilly region called the Emmental. That's named after the Emme River that runs through these foothills of the massive Alps to the south. The well-watered land there can support a grazing and dairying agriculture, but don't look for amber waves of wheat and corn – too cool, humid and hilly for a consistent yield.

|

Swiss Reformed Church at Würzbrunnen near Röthenbach.

Photo credit John E. Engle. |

All Switzerland before the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s participated in the traditions of Roman Catholicism. One important site of

interest to Engels in Canton Bern is the church in Würzbrunnen, now in the town of Röthenbach. Although this particular structure was built later, records state that in 1148 a monastery was located at Würzbrunnen. The faithful traveled here on their pilgrimages to honor St. Wolfgang, a tenth-century German bishop who evangelized the Hungarians. These pilgrimage sites attracted thousands of devoted souls from various parts of Europe and helped the local economy. These Engels had links to Röthenbach.

|

| Statue of Emperor Charlemagne at Swiss Reformed Church in Zurich.

Photo credit: John Ruth, used with permission. |

Although the Middle Ages saw protracted conflict between secular authorities, such as the Holy Roman Emperor and the Catholic popes, they all believed in a vision of society where secular and religious authorities would both promote true faith and eliminate religious heresy. This view is illustrated by a statue of Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor, in the tower of the major church in Zurich, Switzerland. He sits holding the imperial sword, which could symbolize the force used to coerce religious uniformity through violence.

Late medieval society became especially conscious of the discrepancy between the ideal church and the abuses of buying and selling church offices and priests with low moral standards. Various attempts at reform had produced no thoroughgoing changes. This alienated many Christians, especially Martin Luther, the former German monk who was an important leader of the Protestant Reformation in the early 1500s.

We need to describe the religious movement of radical reform in the 1500s known as Anabaptism because the Engel ancestors joined this movement and their subsequent migrations can, in part, be explained because of this. In Europe some Anabaptists later became known as Mennonites and Amish.

|

| Statue of Ulrich Zwingli (with sword) at Swiss Reformed Church in Zurich. Photo credit: John E. Engle. |

Anabaptism originated in three broad areas in Europe – independent of each other: 1) what is now southern Germany and Austria; 2) the Netherlands; and 3) Canton Zurich, Switzerland. In the city of Zurich about 1522 a priest named Ulrich Zwingli led the reform and became known as the father of the Swiss Reformation and the Swiss Reformed Church. Instead of bowing to tradition, he based his theology and his sermons on Biblical texts; he did not find support there for much of what he saw in the church. He led out by refusing to hold the Lenten fast. He celebrated Communion as a memorial meal of Jesus' Last Supper, rather than the Roman Catholic view that the bread and wine theologically became the sacrificed body and blood of Jesus. Among his followers were two young men, Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz. With Zwingli they shared some basic beliefs of the Protestant Reformation:

- Apostles Creed: As shared with most all Christian traditions.

- Primacy of the Scripture: For them the Word of God in the Bible was the final authority, higher than tradition or pope.

- Salvation by Grace through Faith: Faith, they asserted, depends on God's grace more than human action.

- Anti-sacramentalism: They believed that priests or sacraments could not directly and exclusively convey God's grace to humans.

- Anti-clericalism: They decried moral failures of monks and priests.

When Grebel and others urged Zwingli to increase the pace of reform by abolishing infant baptism and the church tithe (a tax to the church that all were forced to pay), Zwingli sought support from the town council. The council did not want to lose the income from the taxes and wanted to control the nature of church reform. Zwingli chose not to abandon infant baptism with its underpinning of a unified religious expression for the state.

By 1525 the Anabaptists had been rejected by Zwingli and the city council. The first clear break was the "illegal" adult baptisms which took place in January 1525 and the full force of state repression was trained on them in the form of imprisonment, banishment, and execution.

On February 24, 1527, Anabaptist leaders met in the Swiss town of Schleitheim and agreed on seven theological articles (named after the town). They briefly outlined the basic points of the Swiss Anabaptist movement at that time. The first three of the Schleitheim Articles were held by most all Anabaptists, but the remaining four were especially held among the Swiss Anabaptists:

1. Adult baptism: Water baptism of adults only after repentance and confession of faith; It meant incorporation into the church – body of Christ on earth. The German term for Anabaptism is Wiedertäufer, which means re-baptize or baptize again. This term was given by their opponents; the Anabaptists did not believe that their adult baptisms were the second baptism – the baptism of infants was, for them, biblically and theologically invalid. In Switzerland the authorities generally called them Täufer (Baptizers) but they called themselves Brüder und Schwester (Brothers and Sisters) .

2. Church discipline with the ban: Church members lived under discipline of community, including the ban or excommunication, which recognizes the church's responsibility to discipline, admonish and correct its members.

3. Communion only for members: Since the Anabaptists viewed communion as both a memorial of Christ's sacrifice and a sign of the obligation to brotherly love, only those committed to supporting each other in concrete ways could take communion together.

The following four were emphasized in Switzerland:

4. Separation from the World: Christians need to have a visible witness and reject the sinful ways of the state-supported churches.

5. Pastors chosen by congregation; The gathered people of God are the primary earthly authority and leaders arise out of the congregation.

6. Biblical pacifism: They believed that Jesus' command to love the enemy and turn the other cheek was the Christian ethic for the present and for all situations – even times when the government demanded joining the army and killing one's enemies.

7. No swearing of oaths: More than a desire to tell the truth at all times, this refusal to swear the oath, demanded by most secular governments, meant that Anabaptists reserved highest allegiance to God.

By early 1527 Zurich had executed the first Swiss Anabaptist martyr, Felix Manz, by drowning in the Limmat River. It soon became apparent that even the major Reformers such as Zwingli and Luther did not want full separation of church and state. They wanted to call on the power of the state to enforce uniformity of religion. In their eyes the Anabaptists were both religious heretics and political revolutionaries. As one contemporary scholar stated, "When the Anabaptists refused to repeat the feudal oath, refused to bear arms, and withdrew from participation in the legally privileged and controlled churches, they struck a radical blow for liberty, conscience and human dignity. Their devotion was directed toward true Christianity rather than social reform, but the secondary consequences of their spiritual emigration were also momentous."

|

Rural scene in Emmental region of Canton Bern showing high Alps to the south.

Photo credit: Eggiwil-Röthenbach Heimatbuch, Verlag Paul Haupt Bern,

permission requested. |

These radical convictions in Zurich about the church soon spread to Canton Bern. When the Anabaptists in the cities of Zurich and Bern felt the brunt of persecution, the movement shifted its locus to the more isolated, rural areas, including the Emmental, which has distinctive house and barn architecture. In 1538 a man named Ulrich Huber from Röthenbach in the Emmental was executed as an Anabaptist heretic. In the Emmental the Anabaptists found some seclusion from the police and also some support from Swiss Reformed members sympathetic to them. Known as Halbtäufer or Half-Anabaptists, these men and women continued to attend the Reformed Church but their admiration for the Anabaptists' ethical lifestyle or familial links to them caused the Half-Anabaptists to shelter and protect the Anabaptists from the secular and religious authorities. In some instances even sheriffs and the judges of the church courts protected Anabaptists in clear legal dereliction of their orders from their superiors.

In 1571, not long after Minister Walti Gerber – who lived near Röthenbach – was executed in 1566, Canton Bern abandoned the death sentence for Anabaptists. However, Canton Zurich continued to execute Anabaptists until 1614, when Minister Hans Landis was beheaded.

|

| Postcard of aerial view of Bern, Switzerland, showing location on Aare River from where

Anabaptist prisoners were banished north via the Rhine River. |

In 1659 the Commission for Anabaptist Affairs was created in Canton Bern in order to oversee the repression of the movement, in addition to distributing the confiscated estates seized from Anabaptists. As more persons joined the Anabaptist movement, the concern of the government became heightened. Between 1669 and 1671 Bernese authorities began to use bribery and espionage to catch, arrest and deport Anabaptists. Later, special taxation of particular towns and even the taking of hostages from particular towns became part of the repertoire of the frustrated government. Such repression increased resentment of Reformed parishioners in the rural areas toward their urban rulers. In 1699 the Anabaptist Commission took a more aggressive role in permanently financing special persons called Anabaptist hunters to flush out the Anabaptists and bring them to justice in Bern.

This intensified persecution by the government resulted in a variety of responses from Anabaptists. One scholar wrote: "Rather than lose their livelihoods, impoverish their families and face the uncertain future of exile, many dissenters responded to sever pressure by compromising with authorities." In some instances Anabaptists avoided situations where they might be questioned or gave vague statements in answer to questions. Also, some but not all believed that a forced oath or recantation was not binding on the believer. Some believed that infant baptism, even though not religiously valid, did no harm. In order to legally pass on their assets to their children, some took their children to be baptized in the Reformed Church. One Anabaptist referred to the baptism of his child: "Whether it was a sacrament or an evil, though, was something he deferred to God."

Anabaptists also fled Canton Bern. Attempting to somehow preserve their resources from being seized by the government, Anabaptists sometimes divested themselves of property and possessions by early division of property among children or quick sale to neighbors. They also wrote letters of credit or mortgages to special administrators, who remained in the Emmental and sent income to those Anabaptists who had fled the canton. In some instances the local authorities surreptitiously allowed, or illegally colluded with, the Anabaptists in these attempts to deflect confiscation by the cantonal authorities.

The more intense the persecution, the more Anabaptists hoped to leave for better situations. In 1671 the government intensified the pressure by requiring that all males fifteen and above take the loyalty oath in small groups so that each one could be heard; hundreds fled Bern to the German Palatinate, east of the Rhine River and to Alsace, west of the Rhine, and to Holland.

|

| Farneren farm near Röthenbach, home of Jost Engel (baptized 1639) and Catherine Reusser, grandparents of Ulrich Engel (baptized 1711). This is the upper house, called Ober Farneren (Upper Farneren). There are several buildings in the general area, each containing Farneren in their names. All of these houses/farms have been rebuilt since the early 1700's.

Photo credit: John E. Engle

|

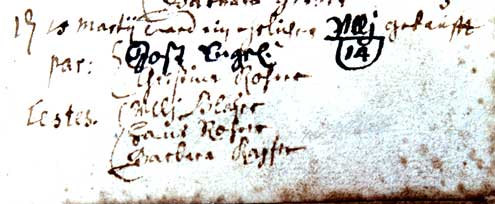

Now to turn to the Engels. We see glimpses of the Engels in Röthenbach area records. The earliest proven ancestors of Immigrant Ulrich Engel (baptized 1711) were Jost Engel and Anna Haldiman, who were married on March 10, 1600, according to church records in nearby Grosshöchstetten. A grandson of Jost and Anna was another Jost Engel (baptized 1639) who moved a few kilometers from a farm called Vorder Schwendi sometime between 1669 and 1674 to the farm called Farneren (here pictured), a part of Röthenbach two kilometers northeast of the village center. In 1678 this Jost Engel requested permission to build an oil mill and press. We assume that this was a press for flax seeds to produce linseed oil.

The first notice of a Röthenbach-area Engel as Anabaptist comes in 1710, when Hans Engel (baptized 1669) was imprisoned with other Anabaptists in Bern on March 6 and deported in that same month. The Anabaptist Commission was interested in the unliquidated properties of Anabaptists such as Hans Engel. Twelve years later several persons were notified by the authorities to appear before the commission on September 15, 1722. One of these was Jost Engel, a brother of this Hans Engel, living on the property known as Farneren. Ulrich, son of Jost, was baptized in 1711. This is the Ulrich, who later emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1754.

|

Entry from Swiss Reformed Church book showing baptism of Ulrich Engel in 1711. Translation: "On the 15th of March, a legitimate (ehelicher) child, Ulli was baptized. Parents: Jost Engel and Christina Rohrer. Witnesses: Ulli Blaser, Hans Rohrer, Barbara Ryser."

Photo credit: Eugene K. Engle |

The percentage of Anabaptists in the general population was probably small, but the government thought them very dangerous because of their impact on Swiss Reformed members; they perceived that Anabaptists weakened the military readiness of the people. The sympathy of these rural Half-Anabaptists was often entwined with a general distrust of changes imposed by the higher church and secular authorities in the city of Bern.

In 1714 the Swiss Reformed preacher in Röthenbach, Johannes Dür, wrote that out of 717 residents, he knew of only three Anabaptists living there and four who had died or left the canton. Although he probably underestimated the number of Anabaptists there, this shows that they were not a majority. He wrote that Anabaptism could never be eliminated from his parish because the Half-Anabaptists were "perjurous" in their efforts to protect them. He wrote that they had their children baptized and sent them to school and catechism. Then, when the children were adults "they just seemed to disappear." Where did they go? We know where some Engels went; they went to the Jura.

Beginning as early as 1538 an area to the northwest of Canton Bern became a place of refuge for the Anabaptists. A map of 1628 shows the location of interest – the Emme River and surrounding area: also the Jura mountains to the northwest of the Emmental where, as we learn later, some Engels fled. Called the Bishopric of Basel until the French Revolution of the late 1700s, this territory in the Jura mountains was administered by the Roman Catholic prince-bishop who resided in Porrentruy. Although not agreeing with their beliefs, the bishop offered semi-toleration and allowed the Anabaptists to settle in certain areas because they could develop agriculture and provide him with tax revenues. The raw climate on these high plateaus and the difficulty of drawing water from wells had discouraged all but the most diligent farmers.

|

1628 map of Canton Bern region, showing Röthenbach (lower right) and (to the northwest) the Jura mountains, to where the Anabaptist Engels fled in 1728 or 1729.

Map courtesy of The Library of Congress |

Following the intense persecutions in Canton Bern in the late 1600s, Bernese Anabaptists, including these Engel ancestors, flooded into the Jura from 1716 to about 1730. In general the landowners who rented to them favored this economic development, but much of the local populace, who spoke French, resented the Swiss-German speaking Anabaptists for displacing them economically and for their religious beliefs. Anabaptists were permitted to rent, not own land, only on the high slopes and plateaus above one thousand meters.

At first the Anabaptists held their worship services in secret out in the open. According to oral tradition, two locations known today were among those used for this purpose. One is called the Goat Church (Geiss-Kirchlein) a cave in a cliff above Le Pichoux in the commune of Souboz. The other is the Anabaptist Bridge (Täufer-Brücke or Le Pont des Anabaptistes) located near the crest of the Cortébertberg.

They created a relief fund administered by the deacons of the church, by which funds and goods were given or loaned to needy church members. Records show that sick or injured or poor persons received funds; in some instances funds were given or loaned to cover immigration costs.

Although the level of harassment in the Jura was less than in the Emmental, life was hard. The thin soil and cool, damp climate restricted the types of crops one could raise. Of course, dairy cattle and making cheese were central to their farming. During the winter, they often plied a trade such as weaving linen, baskets, wood turning, and spinning.

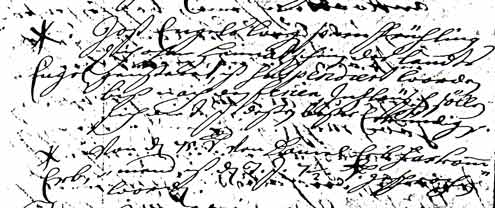

Entries in records of the Anabaptist Commission show that in the Spring of 1727 Jost Engel and his wife Christina Rohrer with their children, including 16-year-old Ulrich, fled Röthenbach without permission and without a certificate of citizenship. They migrated to the Jura by 1728 or 1729.

|

Entry from the Anabaptist Commission (Täufferkammer) record showing that Jost Engel and his family left Röthenbach without permission and without a citizenship certificate.

Photo credit: John E. Engle |

Here we list the family of Jost Engel and Christina Rohrer:

| Jost Engel (1676-1755) m. Christina Rohrer (1675-?) |

| Barbara (1697-?) |

m. Michael Gasser |

| Anna (1700-?) |

m. Daniel Fuhrer/Forrer |

| Catharine (1702-?) |

m1. Mathias Steiner

m2. Peter Oberli |

| Hans (1705-?) |

m1. Barbara Ramseyer

m2. Barbara Gerber |

| Jost (1708-?) |

m. Madlen Brächbühl (1706-?) |

| Ulrich (1711-1757) |

m. Anna Brächbühl (1715-ca1767) |

Christina (1718-?)

|

|

|

Le Cernil farm near Corgémont in the Jura, where Jost and Christina Engel lived by 1741.

Photo credit: John E. Engle. |

Ulrich Engel and Anna Brächbühl married on March 4, 1735 in the Jura. In 1741 Ulrich and Anna were living near Sonceboz. In 1745 Ulrich Engel was noted in records as living on the farm called Le Cernil, near Corgémont, here pictured high above the valley floor. One longer census entry of 1745 refers to Ulrich Engel and his wife Anna Brechbull plus his brother Jost Engel and wife Magdalena Brächbühl as being all Anabaptists. (Brothers married sisters – not the last time that would happen in these close-knit communities). The census describes Ulrich as a bookbinder and rakemaker. We assume that he also did general farming.

Many Anabaptists in the Jura and other parts of Switzerland hoped to leave for better situations.

|

Ulrich Engel and Anna Brächbühl immigrated from the Swiss Jura, probably to Basel on the Rhine River and then to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. They arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1754.

Map courtesy of Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, Lancaster, Pa. |

As their fellow Anabaptists did eighty years earlier, some went to principalities in France, some to the German Palatinate, some to Holland, where wealthy and tolerated fellow Dutch Mennonites lived; and some to Pennsylvania, the rapidly-growing British colony founded by William Penn as a haven or religious toleration and inexpensive land. Later some of the Engels undertook an ocean journey in 1754 from their farm in the Swiss Jura to Pennsylvania.

This provides some context to understand the Engels and how their religious and cultural situation helped God motivate them. In June 2004 I saw the Engel Burial Ground at Wildcat, which sits at the edge of a remote cornfield – most likely the burial location of Ulrich Engel and Anna Brächbühl. About 125 years ago the Engle association built a low stone wall around those gravestones. What foresight. What an inspiring sense of preserving this heritage. Such an act provides a helpful metaphor for family associations – to build a wall around a heritage, high enough to protect it from the ravages of time and low enough to share it with a world in need.

© David Rempel Smucker & EngleFamily.Net, 2004

|